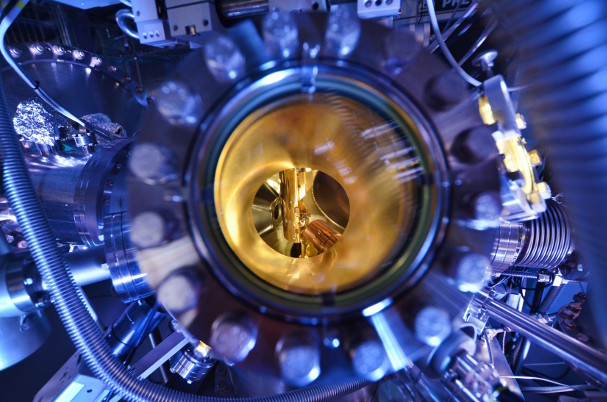

The Solaris Synchrotron at Jagiellonian University in Poland began operating in 2015 and was made possible by generous EU funding. Credit: Anna Wojnar/ Jagiellonian University

Who are the research world's rising stars?

28 July 2016

Anna Wojnar/ Jagiellonian University

The Solaris Synchrotron at Jagiellonian University in Poland began operating in 2015 and was made possible by generous EU funding.

Undaunted by the scientific dominance of historic global big-hitters, some of the world's less prominent research nations are carving out a niche and making a strong impact.

Talent scouts are trained to spot rising stars in the arts, sport and business. These people and organizations may not yet be at the top of their field, but clearly have the potential to shine more brightly than others.

In this spirit, Nature Index 2016 Rising Stars seeks to identify the ascendant performers in the research world, using the power of the Nature Index, which tracks the research of more than 8,000 global institutions.

These institutions and countries have improved their performance often without the longevity, reputation and resources of many well-established institutions that lead academic rankings, such as Harvard and Cambridge universities.

The institutions and countries we examine have increased their contribution to a selection of top natural science journals — a metric known as weighted fractional count (WFC) — from 2012 to 2015. In the competitive world of academic publishing, these are the players to watch.

Several countries we selected as rising stars experienced exceptionally rapid increases during these years, either in their overall WFC, or in the WFC of a specific subject area. For example, the contribution of Indian researchers to chemistry publications grew by 35%. The subject made up more than half the country's output in the index last year.

China's remarkable rise in high-quality research output is now well established, which is why we no longer consider the country a rising star. However, it's worth noting that China topped the list of most improved countries in the index for the past four years, both overall and in the four subject areas tracked by the index: physical sciences, chemistry, life sciences and Earth and environment research.

Russia and Poland were two countries that improved their contribution to the index between 2012 and 2015.

POLAND

2012 WFC: 176.77 2015 WFC: 237.42

Thanks to generous European Union support and a new competitive funding regime, Poland's contribution to the index leapt 34% between 2012 and 2015. The increase can be largely credited to the 2011 creation of the national competitive funding body for basic science, the National Science Centre, and the reform of its applied science counterpart, the National Centre for Research and Development.

“The funds spent on science are now highly competitive. This is a huge change,” says molecular biologist, Maciej Zylicz, president of the Foundation for Polish Science.

As a result, the proportion of funding distributed through competitive grants has risen from 13% before the changes to 45%, or nearly euro 1.8 billion in 2014-15, a trend that is likely to continue as the government moves to have all taxpayer funding of science awarded on the basis of performance.

In practice, these reforms have brought particular gains, mainly in the physical sciences, which has long been Poland's strongest area and which made up more than half of the country's contribution to the index in 2015.

In recent years, Polish scientists have also benefited from new facilities for research. Generous EU funding for research and innovation, euro14 billion between 2007 and 2013, has led to the creation of 10 new international research centres since 2007, including the Solaris Synchrotron at Kraków's Jagiellonian University, which began operation in 2015.

Russia and Poland's rise in the index

RUSSIA

2012 WFC: 298.28 2015 WFC: 370.39

The Russian share of the world's high-quality research increased dramatically between 2012 and 2015. The country's contribution to life sciences in particular grew by more than 60%, the largest percentage rise among the top 10 countries in this field.

These results come at a time of continuing upheaval in the country's science community. Since 2013, the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), a 300-year-old network of more than 500 research institutes, has been undergoing a radical, Kremlin-driven overhaul that many believe will result in the closure of a large swathe of its institutes.

Already, RAS has ceded control of its research priorities and budgets to a separate government agency. And while RAS remains Russia's top producer of high-quality research, its share of the country's index contribution slipped by 2% between 2012 and 2015. Overall, the contribution of Russian scientists to the index increased by 24% over the same period.

By contrast, initiatives to generate quality research outcomes in the university sector are showing signs of success with contributions from the sector driving the country's rising star status. The most ambitious such initiative is the 5-100 Project, launched in 2013 with the aim of pushing five of Russia's top research universities into the top global rankings by 2020.

The project has steered significant additional resources to 21 leading universities. The results are manifest in the index: of the 10 Russian institutions with the highest overall index score, seven are part of the 5-100 programme. Second on the list is St Petersburg's ITMO University, which specializes in IT, optical design and engineering, and saw a leap of 184% in its WFC.

A promovisor reveals a matching ligand being selected for a cancer protein at St Petersburg's ITMO University, which specializes in IT, optical design and engineering. Credit: Margarita Erukova/ITMO University

Research in the physical sciences continues to dominate Russian research, but performance in the life sciences is rapidly improving. The RAS led the gain in quality life sciences publications — an outcome most likely abetted by its absorption of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences and the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences under the 2013 reforms.

Larger economic forces continue to weigh down Russian science activity. In particular, the research community is increasingly feeling the funding pinch caused by the falling oil price and the ongoing domestic economic malaise, says science policy analyst, Irina Dezhina. “The total expenditure on R&D has decreased by 10% this year and there will probably be an additional decrease in the coming year,” Dezhina says.

By Annabel McGilvray