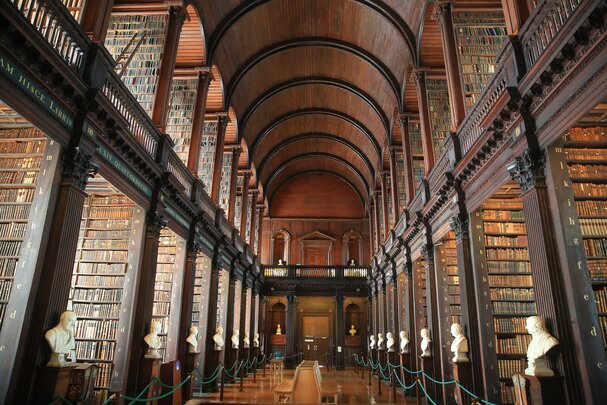

A view of the Long Room in the Trinity College Dublin Old Library.

Credit: Vincent Isore/IP3/Getty Images

Librarians seek more support as research partners

Report highlights lack of institutional recognition of changing librarian roles.

20 September 2021

Vincent Isore/IP3/Getty Images

A view of the Long Room in the Trinity College Dublin Old Library.

Librarians should be given more support and credit for their research contributions, which should be costed into grant proposals, according to Research Libraries UK (RLUK), a consortium of research libraries in the UK and Ireland.

A new report commissioned by RLUK and the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) says libraries are becoming important partners in research, for example, in the work of demonstrating societal impact for the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF).

But as they transition from the position of service provider to research partner, their contributions are not acknowledged by academics and institutions, says Matthew Greenhall, deputy executive director of RLUK. For example, on the evidence of the report, when librarians have been involved as research collaborators, often no value is placed on the time they put in.

“The majority of the engagement has been uncosted,” he says.

Varied contributions

Incorporating research into librarians’ job descriptions and performance reviews, giving awards for research achievements, and providing training opportunities as well as research funding for library staff are among the ways the report suggests institutions can better support their research work.

Andrew Cox, an information scientist the University of Sheffield, co-authored a 2017 report on the future of academic libraries which found that their role is changing rapidly due to increased digital learning, large datasets and digital artefacts.

“Research is changing because of big data, machine learning, AI and data-intensive science,” he says. For librarians, “managing data is as important as managing books,” he says.

Acquiring and managing research data is one of a wide variety of librarian activities which could be termed research, the report found. Others included developing funding applications, generating research ideas, and bringing expertise and skills to digital scholarship, literature review, data and software management, and open access.

Library staff can make significant contributions to public engagement and research impact activities, for instance by co-curating exhibitions with academics, and showcasing research on special collections with public engagement activities in galleries and museums, the report found.

“Research is assessed by reference to impact and libraries are good vectors for impact. That’s definitely made libraries more attractive to academics seeking collaborators,” according to an unnamed academic quoted in the report.

The report was compiled by research consultancy Evidence Base using 72 interviews, 10 case studies, 6 focus groups and 323 survey responses from academics, library staff, funders, university managers and other staff in universities and research organizations in the UK and internationally.

Lack of shared understanding

Library staff “bring a wealth of expertise, skills and insight as collaborators and leaders of research”, the report found. But between library staff and academics, there is a lack of “shared understanding” of what constitutes research.

Matthew Greenhall

Levels of involvement in research will vary depending on institution, project and staff. “The report isn’t suggesting that every library become an academic department,” says Greenhall. “It is highlighting that there is a real contribution there to be made, which isn’t always recognized at the moment,” he says.

For example, a library staff member quoted in the report said systematic reviews, (articles which assess the academic literature to address a research question) are “a really under-appreciated area in which libraries do a lot of genuine research”.

“But sometimes librarians don’t even get credited on them because an academic will commission a systematic review,” the unnamed staff member says. “It’ll get done by a librarian. It’ll go to that publisher with the academic’s name with maybe a footnote mentioning the librarian.”

Effective collaboration

Librarians should be involved in research projects “at an early stage”, the report recommends.

But for library staff, there are “logistical difficulties in writing themselves in, or getting themselves written in, to research funding applications in an equitable way,” says Amelie Roper, a research facilitator at the library at the University of Cambridge, UK. She helps library staff cost in their time and “scope out their contributions and make sure that they're recognized in the application.”

Costing decisions require knowledge of the range of roles in research projects and funding terminology. The also demand a good understanding of “what might count as a service and therefore be covered in overheads attached to costs, and what is distinct from service activity and therefore needs to be included separately” in grant proposals, she says.

“Probably what is needed is more roles like mine, which bridges between the library and the central research office,” says Roper.

Barriers to collaboration

In the report, time and capacity were identified by 93% of library staff surveyed as “significant barriers” to them being actively involved in research, alongside a “lack of confidence” in their own research skills.

One research facilitator was quoted in the report as saying, “If the RLUK really wants librarians to do research, I think we need a different generation of librarians, maybe different contracts.”

But “there can be a lack of institutional support for library staff to be actively involved in research”, the report notes. It is not usually a priority for libraries that are under pressure to meet other targets, related to student experience, for example.

Many library staff are unsure if they are eligible to apply for research funding, and are unaware of UK-based initiatives such as the Technician Commitment, which aims to promote technician roles, and the Hidden REF, a campaign to recognise all research outputs in institutions, the report found.

As a response to the reports’ findings, RLUK is launching a joint Professional Practice Fellowship scheme, worth £100,000, with the AHRC, to help library staff “develop their own research capacity and confidence,” says Greenhall.

Due credit

The report recommends that academics should give library staff credit for their contributions either formally, by naming them as co-investigators or principal investigators on grants, or informally, including through CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy), a framework to recognise individual contributions to outputs such as academic papers.

Caitriona Curtis

“We treat library staff as our academic partners,” says Caitriona Curtis, executive director of Trinity College Dublin’s Long Room Hub, a research institute which operates in partnership with the library and various schools to promote research on the library’s collections. A joint research agenda signed between academics, the library and the institute helped to define priorities and enhance collaboration, she says.

“By bringing our teams together, and letting our researchers and schools know what we're working on, we're able to take advantage of opportunities for fundraising, joint research, philanthropic support, training and workshops, and bringing in visiting fellows,” says Curtis.

Helen Shenton

Helen Shenton, librarian and college archivist at Trinity College Dublin, worked with computer scientists, a professor of drama and other librarians as a co-author on a 2021 study about the use of augmented reality in museum exhibitions.

Looking to other examples of successful research partnerships in the university, Shenton says having embedded librarians who work within a research group is “a very rich way of working, literally, closer together,” and one way to “get recognition”.